EarlyEducationWoodstockTenn.

.jpg)

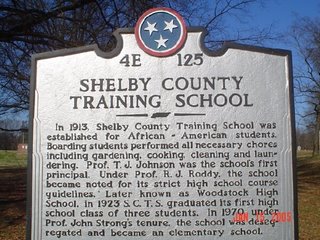

In 1913 Shelby County Training School was established for African-American students. Boarding students performed all necessary chores, including gardening, cooking, cleaning, and laundering. The school would remain segregated for 57 years. Professor T. J. Johnson was the school's first principal. Later the school became known as Woodstock High School. African-American students from elementary school within a 30 mile radius of Woodstock were bussed to Woodstock to finish their high school education. Under Professor R. J. Roddy the school became noted for its strict high school course guidelines. In 1923 it graduated its first high school class of 3 students. In 1964 the graduating class comprised 98 students. The valedictorian was London Steverson, the first graduate to receive an appointment from the United States Coast Guard Academy. In 1970 the school was desegregated. With the admission of white students the school became an elementary school.

The Story of Woodstock High School, Part 2

Graduates Reflect on Historic Mid-South Black School

Last Edited: Thursday, 13 Nov 2008, 5:11 PM CST

Created: Thursday, 13 Nov 2008, 5:11 PM CST

Historical Marker at the site of the Shelby County Training School, which later became Woodstock High School. (Photo credit: cgachasehall.blogspot.com) Les Smith, FOX13 News

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (WHBQ FOX13 myfoxmemphis.com) -- Through the fading decades and succeeding generations, quality education has been the golden thread used to weave an eternal bond between students and teachers at Northwest Shelby County's Woodstock School.

As the school's former vice-principal for 16 years, Vernon Bacon, proudly says, "Woodstock was a family. Just like a family and right now those people that are still living that taught at Woodstock. That went to Woodstock. They still feel the same."

Starting in 1913, the county's first Negro co-educational school, then located on Woodstock-Cuba Road, relied on it's self sufficiency. Boys planted and tended gardens and fields which provided food for students and faculty members living in wooden dorms. Girls put their domestic science skills to use in cooking and sewing. The close-knit atmosphere experienced by teachers and students created a link of caring and concern which extended long past regular school hours.

Willie Marshall Parker explains, "Woodstock was a twelve month school. Even though school was out, we still had teachers on campus that cared and interacted with the students even when school was out."

Memphis businessman, Pat Carter, describes, "If you were having trouble with math, then your math teacher would stay with you. It might be six o'clock or seven o'clock. We're still going over that math."

Parker's sister, Billie Jean, agrees saying, "You got to know the teachers much better and just knew that this was heaven. And it was heaven for Woodstock."

But, in the 1940's and '50's Mid-South, even the educational "heaven" enjoyed at the all-Black school wasn't immune to the prejudices and intrusions from outside its friendly confines. Bacon called "disruptive" a practice the school had no way of stopping.

"The plantation owners would come to the school. If a child came to school his parents brought him to school and they would get him out of class to plant or pick cotton. And I thought that was the worst thing in the world. But, you had no choice back in those days."

However, while missed weeks in the classroom due to "King Cotton" was regarded as a necessary evil, a greater threat to the serenity of Woodstock ironically came through a process meant to expand and improve the quality of education. The successes won in the Civil Rights Movement had inadvertently spawned what would become Woodstock's greatest nemesis and lead to its eventual demise as a high school. Vernon Bacon says the gradual integration of schools in Shelby County led many on the schools devoted faculty to fear calls from the Superintendent's office. He remembers being present when one such call came for a veteran teacher.

Bacon relates, "So when she answered the telephone he was transferring her from Woodstock to a white school. And she just almost passed out. She just fainted almost."

As a student, Carter says "What we thought about it was that we were gonna lose those teachers and that we were gonna be short changed."

Current middle school teacher, Charlotte Smith, remembers how hostility to the changes grew, "The class of 1967..during that year everyone was required to do a senior speech. And they had started to get a little militant. So, it ended that year."

Retired teacher, Trent McVay adds, "We were all disappointed. Not to be going to an integrated school. But, we were disappointed we were having to leave what we thought was a great school. We felt like maybe the other school should be coming to us."

In 1970, with high schoolers sent to Millington, Woodstock became a middle school. But, more than 35 years after those transformations, the commitment to a school that produced many of the leading Black educators, civic leaders, businessmen and athletes in Memphis and the rest of the country remains strong and untarnished. A new generation of teachers continues to spread the gospel of education and moral virtues previously espoused by iconic principal R.J.Roddy to the current Woodstock middle school students.

In response middle school counselor, Adrian Parks Logan, smiles and admits, "We heard a lot about it and a lot about Mr. Roddy and what it meant to be an Aggie. So, when I was going to school it meant a lot of school pride. It meant something to go to school at Woodstock."

Current Phys-Ed teacher, David Jordan, chimes in, "We've all graduated from college. We're still in school completing other degrees and we've all come back here because we want to be here."

One of our trio of young teachers, DeAnna Smith, laments, "Some students aren't getting that love and affection that they need. That's why we always try to keep the networks of communication open."

Carter goes on to reflect, "I think it's so important that you have somebody you can latch on to. Because we all need someone. A need to belong. A desire to achieve. An understanding of hard work's potential rewards. All combined to establish the enduring spirit and pride of a school and a community that still sees itself as one."

Vice-Principal Bacon concludes, "And everywhere we go, I'm talking about teachers now, and we see Woodstock students. They always greet us well and they say that they are what they are because of us. And that's the highest compliment. That's the highest compliment anybody could have."

Labels: President Kennedy's Cadets.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home